Uffizi Gallery in Florence: history, works and curiosities

Our journey to discover one of the most important museums in the world and its masterpieces

After nearly two decades of absence from the scene, one of the protagonists of the Uffizi Gallery's collection of antiquities, the great marble horse, a Roman sculpture datable to the late first and early second centuries AD, returns to “neigh” at the center of the Niobe room on the museum's second floor, exactly where it had towered for a century, from the early 20th century until 2006; and, for the first time, a new lighting system shows in all their rich chromaticism the gigantic paintings by Rubens, Suttermans and Grisoni hanging on the walls, simultaneously giving body and luster to the room's ceiling.

Niobe Hall

Niobe HallSome 90 lamps with minimal energy consumption and very high color rendering make up the intricate system of new lighting in the Sala della Niobe. A system for the first time specifically designed to directly enhance the intensity of the colors of the huge seventeenth- and eighteenth-century canvases by Rubens, Suttermans and Grisoni, while at the same time enriching the architectural elements and gilded decorations of the sumptuous ceiling with a hitherto unseen brilliance. In addition, almost thirty years after their installation, the curtains on the windows have been removed: replacing them are ultraviolet-protecting films, which also allow natural light to enter the room, and visitors to admire views of downtown Florence, in the context of the general reopening of the museum to the city.

Niobe hall, Uffizi

Niobe hall, UffiziThey were built to be offices. Cosimo I wanted them, in 1560 to bring together and keep under control magistracies, arts, economic activities and also reclaim the area unequivocally called La Baldracca.

Giorgio Vasari, will build a unique U-shaped building and five years later will connect, with almost a kilometer of elevated corridor, Palazzo Vecchio to Pitti. Discover our article with video and interview with the director of the Uffizi Gallery Eike Schmidt. As of January 2024, the new director of the Uffizi is in fact Simone Verde, former director of the Complesso Monumentale della Pilotta, whose total restoration and refurbishment he completed, and former Head of Scientific Research and Publications for the Louvre in Abu Dhabi/Afm. (You can read our interview with director Simone Verde here).

Everything recalls Cosimo I: portrayed by Giambologna as an emperor on horseback, by Ammannati as the god of the Seas in Neptune's basin and by Cellini as Perseus who keeps his enemies away by showing Medusa's head. The reopening is scheduled for May 2024.

While the Uffizi immediately became a place of representation. Buontalenti created for his son Francesco the first museum (for a select few) in the Tribuna and for his brother Ferdinando the Teatro di Corte on the second floor. However, it was not until 1765 that Pietro Leopoldo of Lorraine created the first museum open to everyone. Above all, we owe it to Anna Maria Luisa, who in 1737, on the death of her brother Gian Gastone, stipulated a pact with the new grand dukes, committing them not to touch the artistic heritage.

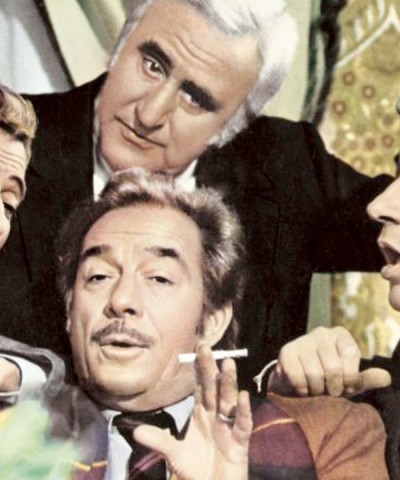

Other reasons to return to the Uffizi are the reopening of the Vasari Corridor (find all the information here) and on the first floor twelve new rooms are dedicated to self-portraits and portraits of artists, from the 15th to the 21st century, including video artists and cartoonists. The itinerary, which offers a selection of more than 250 works, including paintings, sculptures, installations and graphics, is an opportunity to let the great protagonists of art flow before your eyes: among them Andrea del Sarto, Federico Barocci, Luca Giordano, Rubens, Rembrandt, but also Francesco Hayez, Eugène Delacroix, Arnold Böcklin and Marino Marini. Here all the masterpieces in these new rooms are not to be missed.

Autoritratti degli Uffizi

Autoritratti degli UffiziBefore a more in-depth tour of the museum's various rooms, discover our selection of the Uffizi's ten must-see masterpieces, our journey of discovery with Eike Schmidt and our in-depth look at the Boboli Gardens.

Want to discover the other must-see museums in Florence? Click here!

SECOND FLOOR

Right at the entrance to the second floor, after 200 years ‘resurrects’ and returns visible to all, reconstructed in its original form, one of the Uffizi Gallery's most famous spaces dedicated to classical antiquity: the Marble Cabinet, containing a selection of the most important Roman sculptures from the Medici collection and made unique by the series of reliefs set into its walls.

Sala dei Marmi

Sala dei Marmi Among the various works on display are masterpieces such as the two reliefs with cushion and cloth sales from a tomb on the Esquiline from the Flavian period, the figure of a seated shepherd, originally part of a monumental nymphaeum from the early imperial period, or the accurate reproduction of the temple of Vesta flanked by the ruminal fig tree. Magnetic then is the depiction of Zeus Ammon, a syncretic divinity of the Hellenistic Roman period, which formed part of the sculptural decoration of the Forum of Augustus in Rome and is now returned to public view after a long period in storage; the splendid green basalt torso from the Wadi Hammamat, perhaps the best replica of Polyclitus' Doriphorus to date, or the Spinarius, one of seven known copies of this singular late Hellenistic sculptural type, the most famous replica of which is now in the Capitoline Museums in Rome. The space also houses some sculptures that have not been exhibited for a long time: these include the statuette depicting Seated Menander, one of only three known copies of this iconographic model developed in Athens in the 3rd century BC, and the group of Hermaphroditus and Pan, a lively composition from the early imperial period probably created for a garden decoration.

Mappa secondo piano

Mappa secondo pianoEAST CORRIDOR

Giotto and the early 1400s (Rooms A4 - A7)

We start on the second floor, following a chronological development from the late 13th century with the Majesties of Duccio, Cimabue and Giotto emerging powerfully. Do you see her Madonna as she looks at us? How she is alive, how she is mother? The Madonna has prosperous breasts. No one before Giotto had dared to do so much. While the Sienese Duccio opens the chapter of the Gothic Courtesan, the one in vogue in the European courts: elegant and decorative. It is the art that triumphs in the aristocratic Republic of Siena.

As you can understand in front of the Annunciation of Simone Martini: here gold triumphs. The angel has just landed and announces the event to Mary, who withdraws in fear. But the message is engraved in gold like a comic strip. The angel, however, holds an olive branch and not the usual Marian symbol lily, which remains confined in the background. The strangeness is soon revealed: the lily was the emblem of the enemy Florence. And it is still Gothic courtly the favorite of the Florentine lords as Palla Strozzi, who for his chapel in Santa Trinita called Gentile da Fabriano. We are in 1423, the Renaissance art moves the first steps, but the intellectual lover of letters is an aristocrat and so he wants an Adoration overflowing with wealth, his. Every detail is defined with grace and elegance including his portrait.

Masaccio and Filippo Lippi (Rooms A8-A9)

But the wind of the Renaissance is too powerful. Here is Masaccio with the Madonna of the Tickle. It is the heir, a century later, Giotto: his is a real woman playing with her son. The scientific perspective of Brunelleschi finds in Paolo Uccello a passionate follower. In the Disembowelment of Bernardino della Carda in the Battle of San Romano (one of the three great tables also present at the National Gallery in London and the Louvre) made for Lionardo Bartolini Salimbeni then passed to Lorenzo the Magnificent. In the panel the escape routes overlap. It seems that the artist was so interested in perspective that he forgot his marital duties. In the same room we find Domenico Veneziano, Beato Angelico and Filippo Lippi. The Carmelite monk who falls in love with the nun Lucrezia Buti portrayed in the Madonna and Child with Two Angels where the mischievous angel facing us is none other than Filippino. A family portrait that is also a milestone of art. The gold background has given way to the landscape that unfolds from the window where the Madonna, richly dressed, is sitting in profile.

Madonna and Child with Two Angels, filippo lippi

Madonna and Child with Two Angels, filippo lippiPollaiolo and Piero della Francesca (rooms A9- A10)

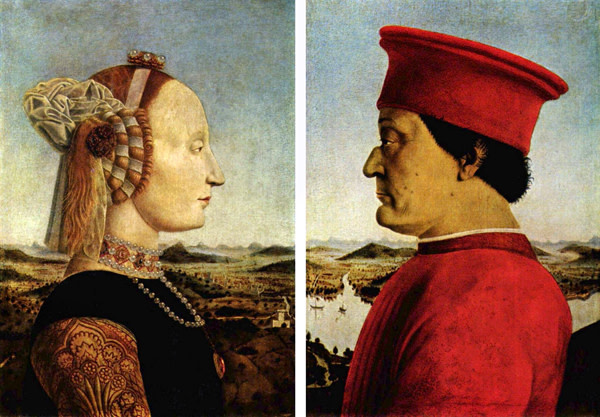

And here we are in the room of the Pollaiolo, where the attention is catalyzed by the diptych of Piero della Francesca with the Dukes of Urbino, we are in 1472. She is Battista Sforza, just died in childbirth, he is Federico da Montefeltro, captain of fortune, leader, patron. Piero depicts the couple (the diptych was closable) in profile as the greats of ancient Rome. But if in her, from the earthly face of death, triumphs the delicacy, the embroidery of clothes and jewelry, in Federico is a succession of volumes. In the background the landscape painted from life.

Double portrait of the Dukes of Urbino, Piero della Francesca

Double portrait of the Dukes of Urbino, Piero della FrancescaSandro Botticelli (rooms A11-A12)

And here is Botticelli. He is the neo-Platonic artist par excellence at the court of the Magnifico. And he tells us about that pagan world that the philosophy of Marsilio Ficino and Pico della Mirandola had actualized. That beauty which is absolute love, contemplative and in fact unattainable. The Spring inspired by Ovid's Metamorphoses and reinterpreted by Agnolo Poliziano for the Rooms, dedicated to Giuliano dei Medici's entrance into society. Uncertain the dating: perhaps the 1478 before the conspiracy or the 1482 year of the recovered peace. Almost certainly the work is commissioned by the Magnificent for the marriage of his cousin Lorenzo with Semiramide Appiani portrayed as Flora. It should be read from right to left with Zephyrus merging with Clori and transforming her into Flora, the goddess of Spring. But Spring is the rebirth of nature and so here is Venus (Fioretta Gorini, mother of the future Pope Clement VII). Above her, Eros, spiteful, blindfolded, randomly shoots a dart towards the Three Graces, with the face of Simonetta Vespucci and finally Mercury, the god of knowledge, perhaps Giuliano, who with a small stick sweeps away the clouds from the Medici sky. And then the Birth of Venus. Realized on canvas almost certainly around 1482 after Botticelli's return from Rome, where he could see a statue of Venus Pudica that he recreates to give body to the essence of platonic love with the face of Simonetta his muse. All-pagan topic? Not really. The shell, Marian symbol, could be the link with Christianity. Here is the Adoration of the Magi with the Medici family in full and the Portinari Triptych by Hugo Van Der Goes that will put the Florentines in contact with the Flemish art, allusive and framed in a bird's eye perspective. And finally, the Tribuna where the most precious works were kept. Made by Buontalenti wants to recreate for Francis the Cosmos. The floor of precious marbles and semi-precious stones evokes the Earth, the vault with six thousand shells of the Indian Ocean and the drum with 2500 mother-of-pearl references to Water, the walls covered with crimson velvet mimic Fire and finally the lantern the Heavens.

spring, sandro botticelli

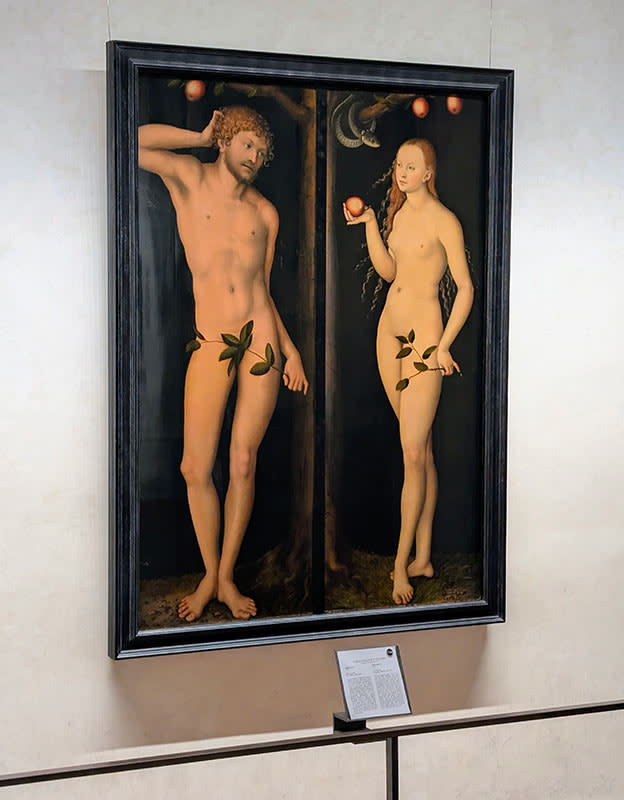

spring, sandro botticelliNot far from the Botticelli masterpieces, a selection of thirty-one paintings, set up in three frescoed rooms tell the 'almost photographic' art of Belgian, Dutch and German painters of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries: among them, Dürer, Cranach, Memling, Froment and Van Der Wyeden. This pictorial nucleus, among the most important in Europe, was brought together in the eastern rooms in the first decades of the last century by Roberto Salvini, director of the Uffizi after World War II, who is credited with placing it in dialogue with the masters of the Italian school, making evident suggestions and mutual influences according to an approach that was then called 'internationalist' and that now would be called 'global' to art history. Today's exhibition intends to re-propose that connection and to illustrate the modes of expression of Renaissance culture in northern Europe-Flanders, Holland, and Germany-in comparison with the works of the Florentine Quattrocento.

Sala dei Fiamminghi

Sala dei FiamminghiAn important new development has just been announced: reunited in a single frame (which also recomposes the two parts of the Tree of Knowledge) are the legendary pair of Adam and Eve panels by the great German painter Lukas Cranach (Kronach, 1472 - Weimar, October 16, 1553), the undisputed protagonists of the new Flemish painters' rooms on the second floor of the Uffizi Gallery. Of the theme of Adam and Eve, the progenitors who fell into temptation condemning humanity, Lukas Cranach painted, with his collaborators, more than fifty versions. The two panels in the Uffizi were conceived as separate works, but designed to stand next to each other, in dialogue, as intuited by the Tree of Knowledge, whose halves are depicted on each of the panels. The new frame, modeled after those in black ebony historically in use in central and northern European collections and fitted with protective glass, visually and aesthetically restores the unity of conception of the pair of paintings and the relationship that comes to be established between Adam and Eve, the gazes and facial expressions of which now converge in a single narrative, in which the parts, divided in the two panels, of the Tree of Knowledge are also recomposed.

Adamo ed Eva, Lukas Cranach

Adamo ed Eva, Lukas CranachSOUTH CORRIDOR

Un meraviglioso affaccio sull'Arno.

WEST CORRIDOR

Leonardo (room A35)

The rooms of the second half of the 15th century open with Ghirlandaio, who takes from the Flemish the care for details and the narration as a chronicler, Perugino, Piero Rosselli and Filippino Lippi and his Adoration of the Magi that in 1496 will replace the work that Leonardo left incomplete in 1482 when he went to Milan to meet Ludovico il Moro. And so we see his Adoration. After a long restoration, the work has revealed unexpected novelties. Like the colored parts. The artist, in his naturalness, captures the deepest feelings of those who witness the birth of the Messiah. There are those who are incredulous, those who are terrified, those who are worried, those who are doubtful. Leonardo experiments here his studies of physiognomy, including a self-portrait. In the distance, a half-destroyed pagan temple and a battle between knights. Thanks to the offset vanishing point, the eye catches all the scenes. In the Annunciation, he introduces aerial perspective. The space is as the human eye perceives it: the distance blurs the contours. Just as he immerses the bodies in nature that take volume through a continuous blur without clear contours. But he also plays with optical effects: the Madonna must be looked at from the right because otherwise she will appear disjointed, with her right arm exaggeratedly long.

Michelangelo and Raffaello (room A38)

And here we are face to face with Michelangelo. At the Uffizi there is only one work, the Tondo Doni. The director of the Museum Eike Schmidt wanted to unite, confirming the chronological and thematic development of the rooms, Michelangelo and Raphael. Sanzio around 1504 arrives in Florence just to see Leonardo engaged in the Battle of Anghiari and Michelangelo in the one of Cascina for Palazzo Vecchio. Michelangelo judges him an unbearable nosy, but Raphael begins with small commissions that performs mainly scopiazza Leonardo. As the Madonna of the Goldfinch and the portraits of the Doni couple. His ability to make everything seemingly simple in reality is the result of a careful study of details and movements in a harmonious balance. The Doni are the same that commission Michelangelo the famous tondo. Unique work on finished board. The form evokes the desco da parto, a tray for the puerpera. It is here that Michelangelo experiments the sculptural painting obtained by combining contrasting colors, primary and iridescent that define powerful muscles on serpentine figures, as in an infinite attempt to free himself from the matter. At the end of the corridor, together with the copy of the Lacoonte by Baccio Bandinelli and also mentioned by Michelangelo in the Tondo Doni, we also find the Porcellino, or rather the Roman copy of a Greek wild boar. The floor leads to the terrace above the Loggia dei Lanzi, once a hanging garden, from which you can almost touch Palazzo Vecchio.

Tondo Doni, Michelangelo

Tondo Doni, MichelangeloFIRST FLOR

Mappa primo piano Uffizi

Mappa primo piano UffiziIf you want, you can go out, passing through the new stairs designed by Natalini that lead directly outside. But if you want to understand a little more about the legacy that the three great masters have left to the art you absolutely have to go back in the lobby that divides the rooms of Leonardo from that of Michelangelo and Raphael and go down to the second floor. After years, the staircase of Buontalenti has been reopened where, intentionally, the sign has been left by a window thrown by the devastating fury of the Mafia bomb at the Georgofili in 1993.

The new rooms. Andrea del Sarto (sala D2), Pontormo e Rosso Fiorentino (sala D4)

The staircase leads to the new rooms opened in 1921. And here the atmosphere becomes intimate, muffled. Small rooms, lined with dark that invite us to look at art with a freer spirit. After all, we find ourselves face to face with the mannerists that the malicious critics of all times have labeled as scripts. Yet it is thanks to their ability to quote and mix, to take inspiration from or copy Raphael, Leonardo and Michelangelo, only to tell their story in a different way, that they have definitively opened the doors to modern art. Fourteen new rooms rearranged with about 130 works, at least a third of which have been in storage for some time. Here we are in the area dedicated to Andrea del Sarto. He is finally given the space necessary to understand how the Florentine artist was inspired both by Leonardo, with the Madonna of the Harpies made in the fateful 1517 (the year of Luther's 99 Theses) firmly placed on the apocalyptic Well of the Abyss and by Michelangelo when, almost at the end of his career, he worked on the majestic Altarpiece of Vallombrosa: the figures are enlarged while the landscape disappears. Instead, he was inspired by Fra Bartolomeo (who in turn had inspired Raphael) Plautilla Nelli, the Dominican nun who, by recovering Fra Bartolomeo's drawings, left a mark in Florence in the clean and severe post-Savonarola art, to whom one of the corridors is dedicated, where the precious and rare monochromes on canvas by Del Sarto and Pontormo stand out. But let's go back for a moment and meet Rosso Fiorentino and Pontorno. Pupils of Del Sarto and emulators, in their own way, of Michelangelo, Raffaello and Leonardo, they add the torment of turbulent years: we are between the Protestant Reformation and the Catholic Counter-Reformation. And although Pontormo, unlike Rosso, was dear to the Medici, both are considered at least strange and not very reassuring. Just as the figures chasing each other in the Dream of Human Life and Allegory of Time, which Venusti and Allori took from a drawing by Michelangelo, are not very reassuring. That of Allori is painted, emulating the master Bronzino, behind one of the very rare portraits of Bianca Cappello.

the rooms of pontormo and rosso fiorentino

the rooms of pontormo and rosso fiorentinoThe rooms of the Roman Cinquecento (D6)

But before the walls turn to green, we must meet Daniele da Volterra, better known as Braghettone for having covered the nudes of Michelangelo, of whom, however, he was a fan so much to take whole figures, such as Elijah in the Desert for example. Or the Charity of Francesco Salviati, which closely resembles the Tondo Doni. We have in fact arrived in the section dedicated to the followers of Michelangelo and Raphael of the Roman period. And among these, in addition to Giulio Romano, who takes the baton from Raphael, there is Sebastiano del Piombo, who will work for Agostino Chigi at the Villa Farnesina together with Raphael, of whom he will become a real antagonist. If in fact the youthful Death of Adonis sees him strongly indebted to the Venetian tonalism of Giorgione and Titian, he will then become more and more emulous of Michelangelo.

Charity, Francesco Salviati

Charity, Francesco SalviatiCorridoio dei Marmi (D7)

And don't be in a hurry to meet Titian, first take a trip to the Marble Corridor (another new addition to the rooms) because you will be amazed by the precious tablets (painted at the time) from the Augustan era where the protagonist is daily life. And the most curious are certainly the furniture seller and the cloth merchant.

Correggio and Parmigianino (room D8)

So here we are among the Emilians, from Correggio to Parmigianino and his incomplete Madonna with the long neck lungo where we find both Raphael and Michelangelo, and above all the ironic Dosso Dossi, certainly the funniest with his Ercole put to shame.

Madonna and Child with Angels (Madonna with the long neck), Parmigianino

Madonna and Child with Angels (Madonna with the long neck), ParmigianinoSala del Pilastro (D15)

It's easy to get caught up in the Sala del Pilastro: the white walls and the bright environment are a magnet. The idea is that of a Renaissance church. In fact, here are some large canvases, mostly rectangular, as indicated by the Council of Trent and representing the brief but significant season of Counter-Reformation art before it was swallowed up in Baroque luminescence. The artists, including a reappeared (after 10 years of oblivion) Madonna del Popolo by Federico Barocci, had to highlight, without the mannerist trappings, the miraculous event that was being talked about, chosen from among the most significant in the life of Christ and the various saints. The rectangular shape had in fact this purpose. The room therefore offers a significant cross-section of the revolution that affected, under Vasari's direction, the Florentine conventual churches in the second half of the 1500s. The ancient altars and partitions were lost, but in compensation the ambitious Duke Cosimo I obtained the title of Grand Duke.

La sala degli autoritratti (sala C14)

Just a taste for now, but the self-portraits will then be part of further new rooms being set up. In the meantime, we can have fun looking at those ancestors of the selfie that from Bernini to Cigoli, and from Anguissola to Vigéè Le Brun to Guttuso and up to Chagall and Yayoi Kusama invite us to imagine them chatting with us.

The Venetians, Tiziano (sala D22), Veronese (sala D25)e Tintoretto (sala D24). Un tributo ai Medici

The new rooms continue with the large spaces dedicated to Venetian tonal art, not before dwelling on Bronzino and the second Mannerists, Vasari in primis and in the room dedicated to the Medici dynasty. Alongside the new display for Titian and his Venus of Urbino, there are now, at long last, works by the theatrical Veronese, the intriguing Giorgione and the complex Tintoretto, who recovers the drawing and darkens the tones. And finally, abandoning Vasari's skepticism, for whom the drawing excelled over everything, we can let ourselves be drawn into that play of colors, of tones on tones that give life to bodies and faces. So there is no lack of naturalists from Veneto, including a very modern Venus of Licinius that is hard to believe is sixteenth century.

In the center the Venus of Urbino of Titian

In the center the Venus of Urbino of TitianArtemisia Gentileschi e Caravaggio (sale D29-D32)

We are now in the seventeenth century and to welcome us is the vindictive Judith intent on beheading Holofernes of the most talented of all Caravaggio: Artemisia Gentileschi. The Roman painter, known for having suffered a rape and a reparative marriage, finds protection in the Florence of Cosimo II. Touching her Judith in which she self-portrays. Its vate is Caravaggio. In the Sacrifice of Isaac Caravaggio uses his filmic technique where the beam of light blocks the most dramatic moment: the Angel that stops Abraham's hand in the act of striking his son. The last work before leaving is the old and tired Galileo portrayed by Giusto Sustermans artist of the court of Ferdinand II.

Caravaggio's Medusa Uffizi Gallery Firenze

Caravaggio's Medusa Uffizi Gallery FirenzeAn unmissable opportunity for those visiting the Uffizi from now until the spring. Until next 30 June, on the ground floor of the Uffizi Gallery we will exceptionally find the main statues of the ancient Medici collection. These include the splendid Venus Medicea. In these spacious rooms it is finally possible to admire them up close, in all their beauty. As the history of the museum tells us, the first works of art to enter the newly completed Vasari complex, back in the 1680s, were the ancient marbles from Cosimo I's collection, which had been kept in the Pitti Palace until then. It was Ferdinando I who had the intuition to place the precious sculptures in the eastern corridor on the top floor, where they could be admired completely bathed in natural light. During the 17th century, the statues and portraits spread, occupying the southern corridor and, with the reign of Cosimo III, also the western one. Cosimo III was also responsible for the intuition of having large antique sculptures placed in the Tribuna. As part of the exhibition, the Venus of the Medicis is finally visible again up close and no longer from a considerable distance, as the ban on public access to the Tribuna has imposed for years; and is once again surrounded by those effigies of Venus, such as the Venus Aurea and the Caelestis, which, until the end of the 18th century, crowned her inside the Tribuna, so much so as to suggest to visitors the impression that this environment was "a little Temple inhabited by Goddesses" ("a little temple inhabited by goddesses", according to Edward Wright, 1730). Other individual replicas of classical marble groups are also placed side by side in the exhibition for the first time: thus, the Dancing Faun of the Tribune rejoins the seated Nymph placed in the second corridor, so as to recompose the group of the Invitation to Dance, one of the masterpieces of Hellenistic statuary of the Micro-Asiatic area. Similarly, the Arrotino, one of the Tribuna's historical guests, can finally be brought closer to the hanging Marsyas in the third corridor, so as to restore unity to the group, which was originally also completed by the figure of Apollo, the original of which can be ascribed to late 3rd century B.C. parchment workshops. Finally, the splendid series of twelve ancient herms with portraits of Greek philosophers, athletes, poets and statesmen, originally intended by Ferdinand I to decorate the garden of the Villa Medici on the Pincio, has been returned to public interest in its entirety.

Venere Celeste e Venere Medici

Venere Celeste e Venere Medici