The Loggia of beauty

From the Priors to the Landsknechts to open-air museum The Loggia della Signoria’s strange destiny

By a twist of fate, the young Cosimo I put his life in the hands of those Landsknecht soldiers against whom he had fiercely fought and who had wound fatally his father Giovanni dalle Bande Nere. The same German mercenaries, in fact, who had sacked Rome in 1527 and laid siege to Florence two years later, would become the guards armed with halberds, swords, pikes and culverins at Cosimo I’s service.

Legend has it that they found themselves camped precariously under Piazza della Signoria’s arched gallery, but the precursors of modern-day foot soldiers were really very well-organized. And the Loggia dei Priori, which would be named Lanzi after them, became their garrison.

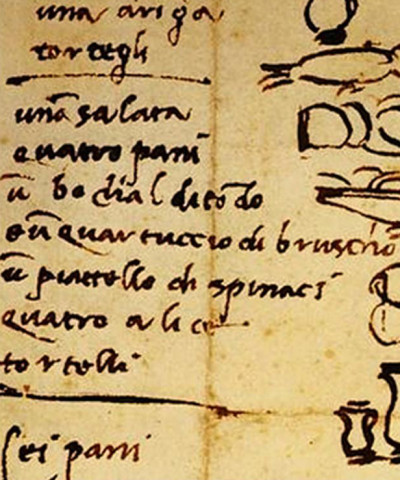

Actually, Cosimo I had inherited the Landsknechts from Alessandro, Florence’s first Duke, who had been killed by his cousin Lorenzino de’ Medici. But while Alessandro had always considered them to be “ugly, dirty and bad”, Cosimo turned the Landsknechts into kind and good-looking people, as shown in the many drawings, paintings and tapestries now on display at the Uffizi Gallery at the exhibition I cento Lanzi del Principe (The Prince’s One Hundred Lanzi), until September 29, which celebrates the 500th anniversary of the birth of the first Grand Duke of Florence.

But when Cosimo brought nearly all Tuscany under his control, leading to a period of peace, even the Lanzi left the Loggia. It was around the time Benvenuto Cellini made the Perseus for Cosimo, the bronze statue with something of the Grand Duke’s features, holding up the Medusa’s severed head in his hand. Though only a bronze statue, it would have kept the enemies at a distance. So, around the mid-1500s, the Loggia began to metamorphose into the world’s first sculpture gallery, open around the clock. As a matter of fact, the statues, which would grow in number over the centuries, are all original.

Under the rule of the Grand Dukes Francesco and Ferdinando, the Loggia was further enriched with the Rape of the Sabine Women by Giambologna and the marble group discovered in Rome, Patroclus and Menelaus, which Pope Pio V had given to Cosimo I. Hercules and the Centaur Nessus, by Giambologna again, was placed under the Loggia in 1812, several years after the classical statues from Roman times - the Sabines and a Germanic princess reduced to slavery, which decorate the back of the Loggia- had been brought here from Villa Medici in Rome. The group The Rape of Polyxena is by Pio Fedi, the only modern sculpture permanently placed in the Loggia, but it was considered to be Fedi’s masterwork and, thus, worthy of public display.

Therefore, a museum in its own right, whose statues are juxtaposed with the others decorating the Piazza. And to think that the Loggia was originally designed to be left empty, just like the Republic of Florence was supposed to be void of secret interests.

The imposing building, in fact, was designed to house public assemblies. It was built in the late 1300s, during the government of the Priors, by purchasing some houses owned by the Bandini and Baroncelli families. And its unusual architectural style is in stark contrast with the rest of the Piazza, with its Gothic pointed arches and Renaissance-style vaulted ceiling. It was designed by Simone Talenti and Benci di Cione, of the Opera del Duomo. The façade was decorated with trefoils housing the four Cardinal Virtues (north) and the Theological Virtues (east). However, the building’s use changed over the centuries, as well as its name: from Loggia dei Priori or della Signoria it became Loggia dell’Orcagna, and finally, in a derogatory way, dei Lanzi. The Loggia is, in fact, the place where the Republic had to submit to the first Medici Duke to rule Florence in 1532 and endure the presence of the Landsknechts, who were also Protestants. The Loggia served also as a sculpture workshop until Ferdinando transformed the roof terrace into a garden from which the Medicis watched the shows held on the Piazza.