2020. The year of Raphael in Florence

Antonio Natali tells us about the great artist in the Florentine disputes on the "manner"

Raphael’s short earthly life, which began in the graceful town of Urbino, ended with his apotheosis in Rome. In order to gain a better understanding of the linguistic difference between the sweetness of his early works and the heroic tone of the paintings he produced in Rome, it is necessary to reflect upon the artist’s stay in Florence between 1504 and 1508, exactly the central years of Florence’s glorious season as the “new Athens”. We need to get a sense of what the city was like in the first decade of the 1500s, in the years of Pier Soderini’s Republic (1502-1512), when the young Raphael roamed the city’s streets, around the same time as Leonardo and Michelangelo, just to mention the best-known artists of the period.

But in order to get a clearer idea of the artistic context in the Florence of the early 1500s, one must recall that in January 1504, shortly after Raphael’s arrival in town, a meeting was held to discuss the permanent location of Michelangelo’s David (which had just been completed). The meeting was attended by the most renowned artists of the time. The list of the artists who convened is impressive. But the names alone, yet as illustrious as they are, are not enough to realize the full extent of the climate in which the artists- “locals and foreigners”, as Vasari would say- lived and worked in Florence. I say “foreigners” because the city attracted artists from all over Italy, both the masters of fourteenth and fifteenth-century painting who had set the precedent and those who saw hope in the artistic patronage of the newborn and ambitious Republic. And, what is more, Florence was the home of fifteenth-century humanism, with all the artists it had created and kept giving birth to: from Brunelleschi, Masaccio, Donatello to Pollaiolo, Verrocchio, Botticelli and Leonardo.

Maddalena Doni, Raffaello

Maddalena Doni, RaffaelloRaphael himself arrived in Florence in search of commissions (which, however, would prove to be of lesser importance), but also to be around whatever new was happening. Five centuries later, it may seem that Massaccio’s Brancacci Chapel had very little influence on a young man such as Raphael, one hundred years after its completion. However, Vasari, who is very reliable when it comes to the 1500s, has no doubt whatsoever about the educational value of Masaccio’s frescoes in the Church of Santa Maria del Carmine even in his own days: “[…] this chapel has been visited by countless masters and those who were practicing their drawing from those time to our own. […] all the most celebrated sculptors and painters who have worked or studied in this chapel have become distinguished and renowned”. And he mentions them all, firstly the masters of the 1400s, and then his contemporaries: “Lionardo da Vinci, Pietro Perugino, fra’ Bartolomeo di San Marco, Mariotto Albertinelli and the most divine Michelagnolo Buonarroti; Raphael of Urbino also developed in the chapel the beginnings of his beautiful style, also Granacci, Lorenzo di Credi, Ridolfo Ghirlandaio, Andrea del Sarto, Rosso Fiorentino, Franciabigio, Baccio Bandinelli, Alonso Spagnolo, Jacopo da Pontormo, Pierino del Vaga and Toto del Nunziata”.

Angelo Doni, Raffaello

Angelo Doni, Raffaello Therefore, Vasari added Raphael to list of the illustrious sixteenth-century artists (which included Berruguete who came from Spain and had dealt with the Florentines) who had studied in the Brancacci chapel. They are more or less the same who, according to Vasari, studied Michelangelo’s cartoon for the Battle of Cascina. Raphael is mentioned as one of the best among the “maniera moderna” artists. Vasari wrote: “ All those who studied the cartoon and sketched from it, which both foreigners and locals continued to do in Florence for many years afterwards, became distinguished individuals in this profession”.

There is, however, a passage in Vasari’s detailed description of that wonderful age which, better than any other, gives an idea of the scale of Florence’s cultural liveliness, which Raphael took actively part in. It is the recollection of the intellectual gatherings held in the workshop of Baccio d’Agnolo, “worker in wood” and a very elegant architect: “there were often gathered round him, in addition to many citizens, the best and most eminent masters of our arts, so that most beautiful conversations and discussions of importance took place there, particularly in winter. The first of these masters was Raffaello da Urbino; then comes a list of other great masters who gathered there, similar to the above-mentioned lists, which ends as follows: “and sometimes, but not often, Michelagnolo, with many young Florentines and foreigners”.

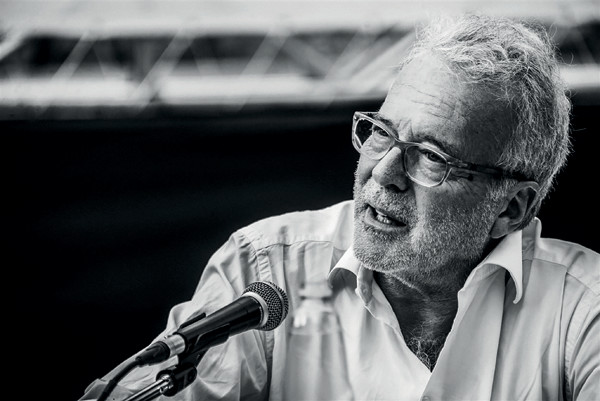

Antonio Natali, specializes in 15th- and 16th-century Tuscan sculpture and painting. From 2006 to 2015 he was the director of the Uffizi Gallery (ph. Antonio Viscido)

Antonio Natali, specializes in 15th- and 16th-century Tuscan sculpture and painting. From 2006 to 2015 he was the director of the Uffizi Gallery (ph. Antonio Viscido)Raphael was thus present (and likely not quiet), while most beautiful conversations and discussions of importance took place, which brought together many citizens and the best and most eminent masters of the arts in Florence. And who were these many citizens who talked to the artists? Who, if not intellectuals interested in discussing culture with artists of high rank? And what beautiful conversations did they have, at a time when a new sensitivity, a new language and a new taste for antiquity, definitely more Hellenistic-oriented, were germinating?

In Florence, the “maniera moderna”, if not born in the workshop of a major artist such as Baccio, definitely found its ideological sanction there. And Raphael - as Vasari confirms - hung about that workshop (and not as second lead), where not only he actively took part in the “discussions of importance” on a form of expression which was undergoing a radical change, but he also brought about a decisive change in his own personal language. In the company of the Florentine masters, Raphael’s delicate early style of Umbrian origin made way for by a more veracious (though still amiable) reading of nature and humanity.