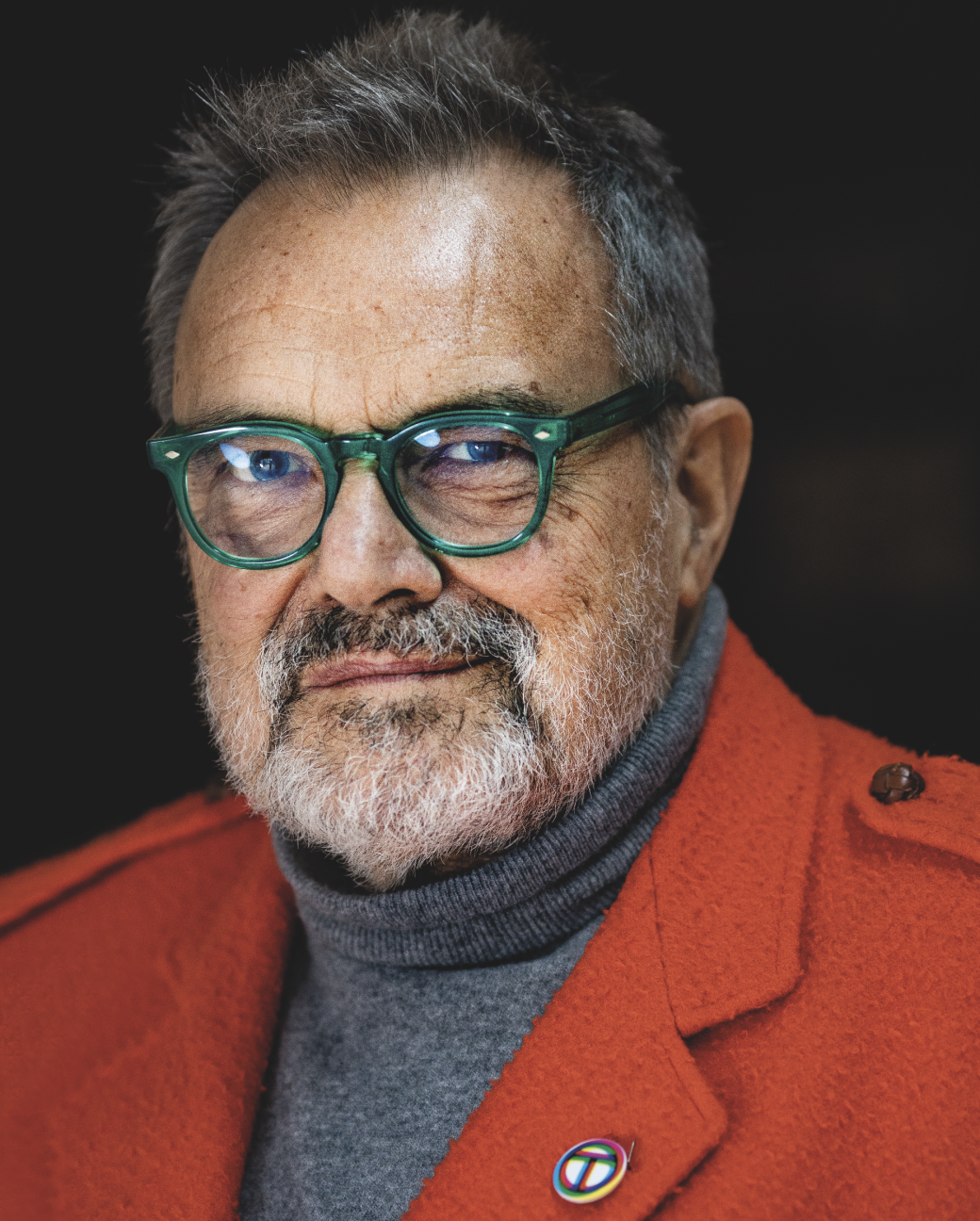

Our interview with Oliviero Toscani

80 years Out from the crowd: face to face with the big photographer

We republish the interview with Oliviero Toscani, conducted at his beloved estate in Casale Marittimo on the occasion of his 80th birthday for the cover of Firenze Made in Tuscany Magazine 62.

His studio, which he built on the estate’s highest elevation, surrounded by vineyards, dominates the view: in front of it, beyond the cypress trees, the sea spreads out with the islands of Corsica, Capraia and Gorgona; further down, to the left, the winery, some farmhouses and his house; to the right, perched on a hill, the small town of Casale Marittimo.

“In 1961, in my first year at the art school in Zürich- Oliviero Toscani tells us- I met a boy called Antonio Tabet who invited me over to his holiday home in Bolgheri. I spent time going around the hills and painting: the olive trees, the landscape. I asked him if I could come back, because I had never felt so attached to a place before. Although Milan is my city, I’ve never been quite fond of it. When, in the late 1960s, my family and I used to vacation on the island of Panarea, my wife asked me to buy a house there, she liked the place. But after thinking it over, I decided that if I was ever to buy a house, it would be in the place where I used to paint as a boy. On September 10, 1970, I showed her this place for the first time. In the eighties, there were no mobile phones, so in order to stay in touch with the rest of the world, I went to Casale where there was a telephone box and I made all my calls from there, with the editors-in-chief of fashion magazines all over the world. That is how I worked the first years. I’ve been living here since then. I took up my residence here in 1972 and mine was the first civil wedding celebrated in the local town hall!”

Oliviero is seated at his desk where, amidst the many books scattered here and there, we catch a glimpse of his autobiography, Ne ho fatte di tutti i colori, released in February by La nave di Teseo, but he is already working on his next book, Die Deutschen des einundzwanzigsten jahrhunderts. He stands up and welcomes us with a broad and rewarding smile on his face: he has just turned 80, but the glint of light in his bright and visionary eyes is that of a boy.

Oliviero Toscani

Oliviero ToscaniWhen you were 30, where did you picture yourself at 80?

At the age of 20, I trusted no one over 30, I looked at the 40-year-olds as old. And to think that now I am the same age as Mick Jagger and Muhammad Ali. People of my generation grew up without knowing how to reach the age of 80. I’m not sure whether it’s a good or bad thing, but had I known that I would live this long, I probably would have taken it easier. I realize that I’ve grown old because my body, this wreck, is not what it used to be.

How did you decide to do this job?

My father worked as a reporter for Corriere della Sera. I grew up in the world of communication. I was, from the outset, more interested in communication than photography- photographers are mere executors, that’s not what I do. When I decided to go down this career path, my father told me that the first thing I had to do was to study both the technique and the art. I attended a school of applied arts in Zürich for five years, a very prestigious school. Photography was born to show the places and people: even if you had never been to Paris, you could see what it was like by looking at pictures of it. The world is conditioned by images, we live on images. Before photography, people were ignorant. 90% of the things we know about, we learned them just by looking at a picture. War, for instance: you’ve never experienced it first-hand but only through images, and yet you are terrified by it. Then, in the 1960s, fashion magazines appeared and photographers were required to have the creativity that was not demanded of reporters. My photography is made up of creativity: I invent, choose, put together. I am an author, a scriptwriter, a film director, the director of photography and also the cameraman. I am the artistic director of myself. Photography is like writing: everyone knows how to write, but not everyone is a writer or a poet. The same goes for photography.

Oliviero Toscani’s studio in Casale Marittimo

Oliviero Toscani’s studio in Casale MarittimoIs portrait photography the way you express yourself?

I’m not a landscape photographer, but I take pictures of whatever has to do with the human condition. I’m unmoved by nature, but when I look at the Cisa (the highway connecting Tuscany, Liguria and Emilia Romagna, editor’s note), I realize how amazing human intervention on nature is. As a photographer, I am a witness of my time. I’m a situationist: I’m interested in the situations around me. The 1960s were the years of press photographers but, instead, I took pictures of Mary Quant’s miniskirt, which changed the world.

You took over 80,000 portraits in your lifetime, but what faces, what people left their mark on you?

The outcasts, those who nobody cares about. Those who just stand there and have no idea why you have any interest in them. Simple people are always ready to help, unlike top models who have never given me anything at all.

Oliviero Toscani’s studio in Casale Marittimo

Oliviero Toscani’s studio in Casale MarittimoLet’s talk about your advertising campaigns. Which was the most difficult one?

In order to understand if and to what extent you are doing something really extreme that will be successful, you need, first of all, to feel uncomfortable about it, because that means that you’re going against your own morality. That’s the moment you actually become interesting. What’s more, you must do something you’ve never done before, by adding elements that no one has ever even conceived possible in that context. And you must not let yourself be influenced by moralists and conformists. If I could go back, I would pay even less attention to those telling me that it’s too much, that I can’t do it, that I don’t pass the politically correct test.

Tuscany is your home. When did you fall in love with this place?

In 1955, my father, mother and I were driving from Milan to Sicily and we stopped in front of Bolgheri’s Viale dei Cipressi. The only poem I had learned in school so far was Davanti a San Guido. Right there, for the first time, I was able to establish a connection between what I had learned in school and the real world. So this place remained stamped in my memory, and I later decided to settle here.

How did you become passionate about horses?

There was this one horse, a Maremma foal, that had been put up for slaughter. My daughter persuaded me to buy it in order to save it. I started looking at it and I made a direct association between that horse and my childhood passion, that is, cowboys and Native Americans. In those years, I was working in California, I went to a horse show at the Cow Palace and I was so impressed by the way they were trained. I started buying horses, many of which became national champions in the United States. When I turned 40, I travelled from New York to Milan with the first two horses I had bought there. We were the first to train American horses and now we have forty of them, among the best horses in Europe. Gennaro Lendi trains here and he is a world champion, the first Italian to become a million dollar rider.

Oliviero Toscani

Oliviero ToscaniYou now have an estate where you produce some excellent wines…

Up to the eighties, wine was not a priority here. In San Francisco, I saw some wonderful vineyards thrive and I asked myself why nobody did it here. One day, a Mr. Masson, a great Bordeaux wine producer, arrived here to look at some racehorses that were bred in the area. Masson gave Mario Incisa della Rocchetta half an hectare of Cabernet Sauvignon vine shoots. He planted them on his estate which borders on the Viale di San Guido. In the beginning, he gave the wine to his friends, until it was sent to a wine competition and awarded. But Cavallari is the man who invented Bolgheri. Pier Mario Meletti Cavallari ended up here with Veronelli by pure chance and bought Grattamacco.

We do not know if Bolgheri’s legendary wine revolution was the result of a gift or of the perseverance of Marchese Incisa della Rocchetta ( as he himself writes in the famous letter to Veronelli), but we could have spent the whole day listening to Oliviero’s stories about Tuscany. Once again, he lives up to his reputation of always standing out of the crowd.