Bargello Museum: history and must-see works

Our tour inside this precious treasure chest of art in Florence

News today of a new Donatello for the Museo Nazionale del Bargello. The Madonna di via Pietrapiana, a terracotta by the master dating from around 1450-1455 and the only autograph work by Donatello that until recently was still privately owned, has been purchased by the Ministry of Culture, assigned to the collections of the Museo Nazionale del Bargello and permanently installed in the prestigious Salone di Donatello, the monumental room that houses the sculptor's masterpieces. The Madonna di via Pietrapiana was recognised as an autograph in 1986 by Charles Avery and was also considered as such by later critics. In the same 1986, it was exhibited at the exhibition Donatello and His. Florentine Sculpture of the Early Renaissance at Forte Belvedere. The work was exhibited for the first time at the Museo Nazionale del Bargello in 2009, on the occasion of the exhibition I Grandi bronzi del Battistero. Giovan Francesco Rustici and Leonardo.

Firenze, Madonna di via Pietrapiana

Firenze, Madonna di via PietrapianaIf one reaches it from the north, along Via del Proconsolo, the Bargello appears to us in all its somewhat sinister severity. Its dismal past as a prison for political prisoners resurfaces despite the fact that today it holds with the Victoria & Albert in London and the Cluny in Paris the primacy of the so-called minor or decorative arts. But it is thanks above all to Dante, who moreover suffered a death sentence in absentia and perpetual exile here, and to the slightly younger Giotto, who perhaps for this very reason wished to remember him by giving history his first portrait, that the palace was chosen as the first national museum of Florence Capital. And today it is only here that one can compare the experimental verve of Donatello with the mightiness of Michelangelo. Support one or the other.

Museo Nazionale del Bargello

Museo Nazionale del BargelloHISTORY

It should be remembered, however, that the Bargello (hence the term sbirro), was built to represent the free ordinary citizen. Indeed, it was here that the Podestà and Capitano del popolo (head of state and government) worked and lived. It was built in the mid-1200s when the city, despite the struggles between the Guelphs and Ghibellines, was experiencing the most dazzling century of its history. So no sooner had Lapo di Cambio completed the city's first public palace than Florence was already entrusting his son Arnolfo with the construction of the new palazzo podestarile that would later belong to the Signoria. And at the Bargello justice will continue to be administered in this way. And it is here that political prisoners begin to end up. And it is also here, that ever since the expulsion of the Duke Gualtieri of Brienne that we hear of the so-called infamous paintings. He is in fact the first to end up portrayed upside down thanks to the happy hand of Giottino. And for centuries the north wall of the Torre Volognana, left purposely plastered, is painted with portraits of the wanted by the most experienced artists, including Botticelli and Andrea del Castagno who gets the nickname Andreino degli impiccati and later Pontormo. Trials were held and death sentences carried out in the Bargello where today a pit replaces the old gallows. Often the condemned are then left hanging outside or their severed heads resting on stumps along the way. It was on his way home that on the evening of December 29, 1479, a young Leonardo stopped to immortalize Bernardo Bandini Baroncelli, who had participated in the Pazzi Conspiracy the year before and was now dangling at a window in the Bargello. Strident is the painstaking description of the hanged man's rich and colorful robes. The step to grim imprisonment is a short one. With the Medici duchy, the Bargello was completely transformed. The Audience Hall, now by Donatello, is divided into four floors with as many as 32 cells and an oratory; the Magdalene Chapel also suffers a similar fate. In the courtyard capital punishments are carried out accompanied by the tolling of the Montanina, the tower bell that today rings only on extraordinary occasions (for the liberation of Florence in '44 and at the passage of the new millennium).

It would indeed have to wait for the enlightened Pietro Leopoldodi Lorena, who in 1786 with a great bonfire of the instruments of torture put an end, first in Europe, to capital punishment. But it was mainly thanks to the obstinacy of a group of passionate devotees of Dante and Giotto who wanted to find Giotto's fresco of Dante's face covered by layers of lime, that in the 1840s research began until the frescoes were eventually found. And with the 1857 transfer of all prisons to the former Convento delle Murate, the Bargello also underwent restoration. When Florence became the capital of the new kingdom of the three centuries of torture and pain there was no longer a trace: the great mullioned window on Piazza San Firenze had been reopened, the Salone delle Udienze recovered, so had the Chapel and the Verone, built in the 1300s, thanks to the proceeds of gambling fines finally reopened. So the Bargello became a museum: the occasion was the exhibition dedicated to the sixth centenary of Dante whose portrait stood out in the Magdalene Chapel. And then the exhibition dedicated to Donatello in 1886 for the fifth anniversary of his birth and Louis Carrand's bequest the following year, to which were then added the Franchetti, Ressman and Bruzichelli donations transformed the Bargello into the precious casket we admire today. And we have only to visit it.

FIRST FLOOR

It is worth climbing the 14th-century staircase by Neri di Fioravante that leads up to the Verone where we are greeted by Giambologna's bronze birds and a late 16th-century marble sculpture by his pupil Francavilla. It is worth pausing in front of the Turkey that the great Flemish mannerist made in bronze in the second half of the 1500s, thus also making it very famous. The animal, originally from America was still almost unknown.

And here we are in the Salone di Donatello (the small room of 14th-century sculpture and the adjoining majolica room are currently under restoration) where the most important sculptures of the artist who will initiate Renaissance art are preserved. And here one can see its stylistic evolution starting with the first David, in marble, which he probably made for a spur of the Duomo around 1408 and which, however, immediately entered the collection of Palazzo Vecchio, with some modifications that Donatello made making it more civic than liturgical. The David was in fact the emblem of civic freedom. But it is still anchored in the Gothic style. It was in fact with the slightly later (1416) St. George, commissioned by the Arte dei Corazzai e Spadai who owned a niche outside Orsanmichele that Donatello inaugurated the Renaissance season. We can see it in the twisting of the body that follows the principles of classical contrapposto art (which Donatello was able to study in Rome where he accompanied his friend Brunelleschi), in the naturalness of the figure, which is imagined well despite the armor, and the proud expression of the face, which moreover will inspire Michelangelo greatly for his David, that make us understand that something, much, has changed. And it is especially in the predella, where the artist applies scientific perspective, complete with vanishing point, and emphasizes it using the ancient technique of stiacciato that a new era opens up. Donatello does not just copy ancient techniques but bends them to new concepts. And since Brunelleschi was mentioned how can we not compare his tile with the Sacrifice ofIsaac with the similar one by Ghiberti. It is 1401 and the Arte di Calimala is holding a competition for the second bronze door of the Baptistery (the first had been made by Andrea Pisano some sixty years earlier). The only limit imposed: respect the polylobate shape, in clear Gothic style, of the tile. Competing for the final outcome will be Ghiberti and Brunelleschi. The latter will lose although more innovative. Indeed, he introduces the vanishing point and the immanence of action: the angel blocking Abraham's hand, which many years later Caravaggio would also do. But the tile by Ghiberti, an experienced goldsmith, not only pleases more because it is more graceful but also turns out to be much less expensive. In fact, Ghiberti ensures that he uses less bronze. But it will also be Brunelleschi's good fortune that disappointed he will leave for Rome where he will draw heavily from classical art. His friend Donatello meanwhile is increasingly famous. And among his most famous works, in addition to the mysterious Atis (or Mercury, since he has winged feet?)Stands perhaps the most beautiful work: the bronze David. Commissioned from him by Cosimo Il Vecchio in 1440it made a fine display in the courtyard of the Palazzo Medici until with the Medici's ouster it was brought to the Palazzo della Signoria. It is the first modern work of nude in the round. A choice to highlight humility and courage. Inspired of course by Roman art. Donatello's David is echoed by the smarmy teenager who shows himself instead with boldness after the heroic act. It is the work commissioned by Piero il Gottoso from Verrocchio. The bronze was later sold to the Signoria by brothers Lorenzo and Giuliano. And Verrocchio thus had to move, for reasons of space, the Goliath's head in front of the young man's feet. Not to be missed, in addition to the caissons and the bust of Niccolò da Uzzano recently attributed to Desiderio da Settignano, is Bertoldo di Giovanni's bas-relief with the Battle between Romans and Barbarians. Donatello's pupil and head of the Garden of San Marco clearly inspired his young pupil Michelangelo.

From 5 June until October, the hall is closed to the public for restoration and refitting.

BRONZES, IVORIES AND CARRAND COLLECTION

As we leave the Donatello Hall, we are greeted by the intimate and soft atmosphere of the Islamic Room, where the precious carpets from the Franchetti Collection are housed and where a number of bronzes and ivories of Islamic and Oriental origin stand out, including an ebony casket with semi-precious stones and silverware. But one must enter the adjoining Carrand Room to lose oneself in the beauty of the objects on display. The bust of Louis Carrand does the honors. Together with his father, wealthy merchants and collectors from Lyon, they moved to Nice and from there expatriated, due to political disagreements, to Italy, first to Pisa and then to Florence. Louis would leave his valuable collection of more than 3,300 pieces of decorative art to the museum. It is a unique heritage and one that has brought the Bargello up to the level of far better-stocked museums such as the Victoria & Albert and the Cluny. Each object of the rest is more unique than rare. But among the most valuable items is surely Agilulf's famous gilded copper plate. The plate dating from the 6th-7th centuries decorated the Longobard king's helmet. So equally valuable are the gilded bronze aquamaniles. One in particular with St. George and the dragon, from the 15th century, is striking for the agility of the little figure and the power of the horse. The aquamanili were used for washing fingers before and after a meal. Beautiful then is the 16th-century embroidered leather scarsella. Before entering the Hall of Ivories, however, we find the Magdalene Chapel with the Paradise where Dante is depicted restored for the 700th anniversary of his death in 2021. On the walls are the stories of St. John, Mary Magdalene and St. Mary of Egypt, characters expressing penitents, while in the center stands a splendid inlaid Olivetan Badalone that was used for liturgical chants. But it is in the adjoining Hall of Ivories that we encounter truly unique pieces such as the liturgical flail from the time of Carlo il Calvo (9th century) that has come down to us virtually intact. It is rightly considered unique. Made of painted parchment it is also fitted with a carved bone handle. And again a splendid Chessboard in ivory and ebony and the Pastoral Hedgehog thought to have belonged to St. Ivo, abbot of Saint Quentin de Beauvais and later bishop of Chartres. Also of rare beauty is the Oliphant, a kind of hunting horn, but one that was played during Holy Week when bells could not be used. Of Norwegian origin from the 13th century, it is carved from a walrus tusk and finely historiated. Among the paintings on display, one cannot fail to admire the Money Changer with his wife of Dutch Reformed art in which the greed of the two is detailed in the Flemish manner.

It is time to go up one more floor and admire the glazed terracottas of the Della Robbia and Buglione families.

Andrea Della Robbia

Andrea Della RobbiaSECOND FLOOR

Here we are immediately in the Hall of Giovanni della Robbia. The son of Andrea and grandson of Luca (whose works, including the small Madonna of the Apple are in Donatello's room), he is also the last member of a family of sculptors and later ceramists who became famous thanks to the technique of glazing majolica. The not-quite-known procedure (the formula spied by the Buglioni was never clarified) consisted of re-glazing the ware at a very high temperature. With glazing, ceramics became very durable and could also be made for outdoor use. With the Della Robbias, however, we also enter modernity. Indeed, serial manufacture is introduced: the preparatory cast could be reused several times, so that mass-produced pieces could be produced. With the result of lowering costs and widening the sphere of buyers. Over the years Luca's blue and white was joined by more colors until the garish ceramics of Giovanni and the Buglioni. Through the small room dedicated to Andrea della Robbia and his delicate portraits, we enter the Hall of Verrocchio and late 15th-century sculpture where we can see what the figures who have marked part of history really looked like. Lots of portrait busts. In addition to Verrocchio, with his Lady with a Small Bouquet most likely Lucrezia Donati's inspirational lady of the Magnifico, the funeral bust of Battista Sforza duchess of Urbino by Francesco Laurana, the merchant Piero Mellini by Benedetto da Maiano, and AntonioPalmieri by Antonio Rossellino. And last but not least the Francesco Sassetti from Verrocchio's workshop, the young man in jousting armor by Antonio del Pollaiolo, and finally Piero il Gottoso by Mino da Fiesole. The roundup of illustrious figures is over, and it is time to return to the courtyard and enter the 16th century. But not before visiting the beautiful Sala dei Bronzetti whose opening is alternated with the nearby rich Sala delle Armi. Unfortunately, the Hall of Medals is closed where the one celebrating the Pazzi Conspiracy by Bertoldo di Giovanni is also kept.

COURTYARD AND HALL OF MICHELANGELO

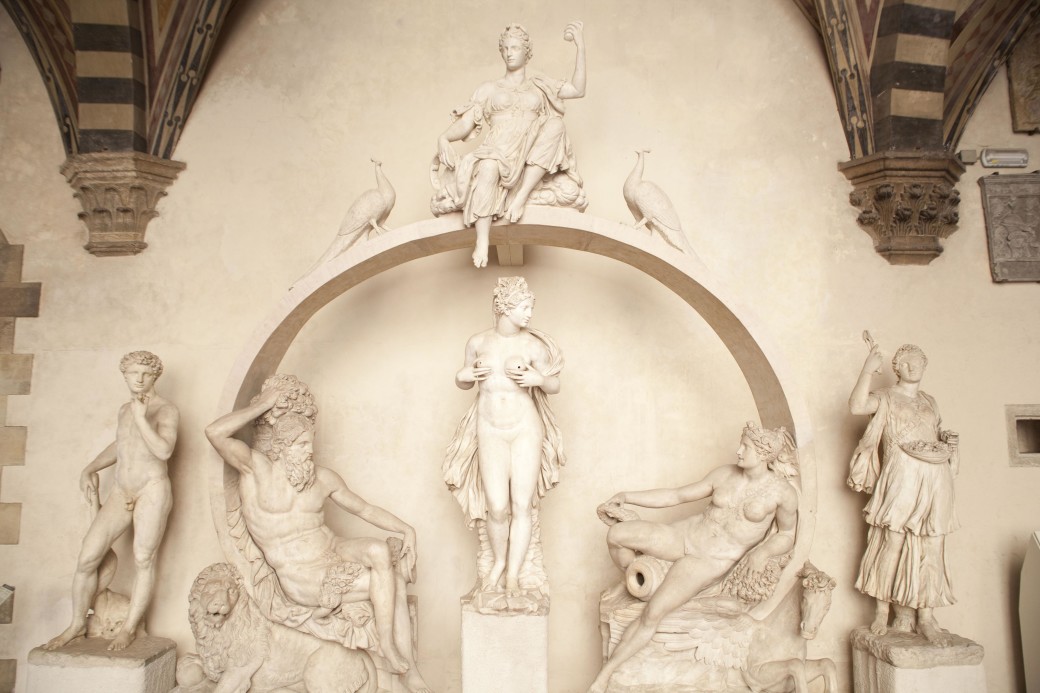

We descend the internal staircase and arrive in the Courtyard, now a pleasant and relaxing space where we can pause. And even here there is no shortage of great works of art such as, for example, the Fountain of the Great Hall that Bartolomeo Ammannati never completed. The complex of allegorical statues with the Arno, Juno, Temperance and even the Fountain of Parnassus was to decorate a wall of the Salone dei Cinquecento in the Palazzo Vecchio but never got there.

Bartolomeo ammannati, fontana di sala grande

Bartolomeo ammannati, fontana di sala grandeIn compensation it was first taken to Pratolino and then reassembled as the Fountain at the Pitti Palace on the occasion of Ferdinand I's wedding and then again dispersed here and there until it was finally reassembled in the museum's Cortile in 2011, on the occasion of the exhibition for the fifth centenary of the artist's birth. It is nevertheless considered the masterpiece of the artist follower of Michelangelo and author of, among other things, the Fountain of Neptune in Piazza Signoria. And before entering Michelangelo's hall it is worth pausing, turning your back to the well that replaces the ancient gallows, in front of the great bronze Cannon of St. Paul commissioned by Ferdinand II from Cosimo Cenni and destined for the Livorno Fortress. But it is the only one of a battery that should have numbered as many as twelve and was never made. The name comes from the saint's head depicted on the breech, while the shaft is decorated with the Medici coat of arms and the allegorical figures of Justice and Strength. And as for strength, he seems to have it to spare when it comes to the gigantic statue depicting Oceano that was commissioned from Giambologna by Cosimo I for a fountain. And in fact until the early 1900s it towered at the apex of the great Fontana dell'Isolotto in Pitti. So here we are in the grand hall where upon entering on the right wall is a Madonna and Child that some scholars think might have been part of the fresco complex of the Magdalene Chapel. But it is Michelangelo's statues that first catch the eye. Not least because they are his most youthful works. In particular the Pitti Tondo and the Bacchus.

Bacco di Giambologna

Bacco di GiambolognaFor the latter, luck would have it that Cardinal Raffaele Riario, who had commissioned the statue in 1496 upon Michelangelo's arrival in Rome, did not appreciate its precarious balance of a decidedly drunken Bacchus. So he sold it to the banker Jacopo Galli, who then sold it to the Medici in 1570. And it was precisely that precarious balance of the Bacchus that fascinated Vasari, who praised its moving beyond classical art toward the tormented movement that would later characterize the artist's mature art. And he seems to measure himself against Donatello when he makes, on behalf of the merchant Bartolomeo Pitti and in the aftermath of the successes of the David, the tondo depicting the Madonna and Child. Here, in fact, Michelangelo intervenes by playing and with stiacciato in the barely sketched figure of the San Giovannino and with perspective by alternating perfectly smooth parts with decidedly rough ones. It did not bring Baccio Valori luck, on the other hand, the Apollo-David that the leader of the papal troops commissioned from Michelangelo in order to give it to the Medici and thus make up for his betrayal for having passed, on the death of the first duke Alessandro, as a follower of the Republic. In reality the work would reach the Medici but with the confiscation of Valori's property, who in the meantime had him beheaded by Cosimo I. However, the work is somewhat ambiguous: is it an Apollo unleashing an arrow or in a David cocking a sling? The triumph of the unfinished leaves the rebus unresolved. While the physiognomy of the Tuscan Brute is very clear. Commissioned from Michelangelo by Donato Giannotti as fierce anti-Medicean republican as the artist himself, the Brute would be that Lorenzino who kills his cousin Alexander and would reopen the republican hopes of anti-Medicean Florentines. Clearly celebratory, on the other hand, are the busts of Cosimo I made by Baccio Bandinelli, the most popular and by Benvenuto Cellini the one most criticized by the grand duke. But by the great goldsmith, sculptor and writer long in the service of and King Francis I of France and Grand Duke Cosimo I at the Bargello is preserved the original base of the Perseus whose statue was made at Cosimo's own behest for the Loggia dei Lanzi and where it still stands in original. The bronzes with allegories related to Perseus allude to the defeat of enemies in the name of virtue and divine justice. Not surprisingly, the head of Perseus resembles the face of Cosimo. And among the most valuable works, one cannot fail to admire Giambologna's Flying Mercury. This is one of the Flemish artist's most prized works and he completed it around 1580, both for the agility of its movements and for the casting technique that required a certain skill. The artist, who is considered the first Mannerist sculptor, not only succeeded in Florence in creating a talented workshop that included Pietro Tacca, Antonio Susini, and Pietro Francavilla, but also in making it clear that the search was by no means over with Michelangelo and that sculpture could go beyond Buonarroti himself, as Gian Lorenzo Bernini would soon prove. Of the Baroque artist the Bargello has the intense portrait of Costanza Bonarelli. Wife of one of Bernini's collaborators, mistress first to Gian Lorenzo and then to his brother Luigi she will be made a scar by the jealous artist. She has an intense and sensual expression. The portrait was for private use, beautiful but also as a perpetual stain that marks if not the art the consideration of the man Bernini. Obviously in our eyes since the artist got off with a small fine.